The Porcupine's Quill

Celebrating forty years on the Main Street

of Erin Village, Wellington County

BOOKS IN PRINT

The Essential Don Coles by Don Coles and Robyn Sarah

Don Coles’ Forests of the Medieval World (PQL 1993) won the Governor General’s Award for poetry. Kurgan (PQL 2000) won the Trillum Prize in Ontario. The Essential Don Coles presents an affordable collection of the poet’s very best work.

The third in a celebrated Porcupine’s Quill series of ‘Essential Poets’ that already includes The Essential George Johnston (2007), and The Essential P. K. Page (2008). Volumes in preparation include The Essential Margaret Avison, The Essential James Reaney and The Essential Richard Outram, amongst others.

2010—ReLit Award,

Long-listed

Table of contents

[Sometimes All Over, 1975]

Photograph in a Stockholm Newspaper...

Divorced Child

How We All Swiftly

Death of Woman

[Anniversaries, 1979]

Sampling from a Dialogue

William, Etc

Codger

Not Just Words but World

Gull Lake, Alta.

[The Prinzhorn Collection, 1982]

The Prinzhorn Collection

Mishenka, from Tolstoy Poems

Major Hoople

Abandoned Lover

Abrupt Daylight Sadness

(from) Landslides I, IV, V, VIII, (X), XI

[Landslides, 1986]

Walking in the Snowy Night

Somewhere Far from this Comfort

[Forests of the Medieval World, 1993]

My Son at the Seashore, Age Two

Someone Has Stayed in Stockholm

Forests of the Medieval World

My Death as the Wren Library

Self-portrait at 3:15 a.m.

Untitled

[Kurgan, 2000]

Kingdom

Marie Kemp

Flowers in an Odd Time

Reading a Biography of Samuel Beckett

Nurseryschoolers

On a Caspar David Friedrich Painting

Botanical Gardens

Review quote

‘Poetic pragmatism is a strong element of Don Coles’ poetry. Coles’ voice, according to critic Robyn Sarah, is ‘‘civilized yet informal,’’ for Coles neglects any attempt to ‘‘primp’’ and aestheticize his language.’

—Alexis Foo, Canadian Literature

Review quote

‘Poetic pragmatism is a strong element of Don Coles’ poetry. Coles’ voice, according to critic Robyn Sarah, is ‘‘civilized yet informal,’’ for Coles neglects any attempt to ‘‘primp’’ and aestheticize his language. Though Coles’ raw honesty throughout The Essential Don Coles resonates with a confidence in the power of the immediacy of thought and impression over aesthetics, many of the early poems from The Prinzhorn Collection (1982) lose their vocal momentum. Despite its fascinating content, the title poem of the collection gets lost in its own lyricism. Though the poem divulges the cognitive layers of the speaker’s experience, the purposefully choppy lines become unmemorable. ‘‘Of course Munch / was called mad too. I have always / felt I knew what to think about that.’’

‘The poems from Landslides (1986), however, capture the confessional essence of the ‘‘I’’ voice while maintaining a lingering sharpness in the lines. In ‘‘Walking in a Snowy Night,’’ the pensive speaker ponders the purifying effect of the white night through which he walks. ‘‘I needed to renew myself like this with silence / and with thinking of you.’’ Coles successfully integrates the authenticity of informal speech with the sentimentality of the moment. The terrain of ‘‘Forests of the Medieval World’’ from the 1993 collection of the same name invokes a mythological history through which the speaker navigates while lamenting the distance between himself and a lover. Within the volatility of Coles’ subjects remains a quiet beauty that is both mildly elegiac and accepting.’

—Alexis Foo, Canadian Literature

Review quote

‘The Essential Don Coles, with a perceptive foreword by Robyn Sarah, is an important book, in spite of its smallness.... I can not think of a better introduction to a poet who will be increasingly recognized as one of the best of our era. The exactness, the ‘odd’ nobility, the depth of understanding, the quitness, the tenderness, the plain but carefully nuanced style, and, above all, the beauty of Coles’s work, places him, to my mind, in the company of Matthew Arnold and WIlliam Stafford.’

—M. Travis Lane, The Fiddlehead

Review quote

‘If the Essential Don Coles is an incomplete document, it is nonetheless a useful document (and beautiful, too). It consolidates Coles’ achievement to date in a way that will help readers to consider his new work in the context of what has come before. And it presents a fairly complete picture of Coles’ achievement in the shorter-lyric mode -- though I’ll make the case that Coles’ longer lyrics (and there are many such in Where We Might Have Been) form a no less essential part of his oeuvre.

This is the second of three ‘‘essentials’’ that Robyn Sarah has edited for the Quill. (The others are The Essential George Johnston and The Essential Margaret Avison.) She does a good job of it. Her foreword is admirably brief, and mostly practical: she gives us a sense of how she made her choices; she points to the notable omissions; she tells us how she has handled variant texts. She’s not afraid to adopt a critical voice, as well. Writing out of a long and intimate acquaintance with Coles’ work, she gives us a sense of his great themes (theme, really: time’s passage) and his stylistic predilections. Then she gets out of the way, so that the poems can speak for themselves.’

—Amanda Jernigan, Arc Poetry Magazine

Review quote

‘Coles is fun to imitate, but no one does Coles like Coles. In both style and substance, he’s at once instantly recognizable and always surprising.’—Stephanie Bolster

Excerpt from book

Forests of the Medieval World

Forests of the medieval world, that’s

where her mind will wander

the three dissertation years, lucky girl --

Forest of Bleu, which crowded around

the walls of Paris and stretched 10,000 leagues

in every direction; the great Hercynian forests

of East Prussia, from which each year

334 drovers bore the logs for the fires

in the Grand Duke’s castles of Rostock,

of Danzig and, furthest east of all, guarding

the borders towards the Polish marshes,

Greifswald and Wolgast. I’m so sad

I could die, you said as you left, but

my children, how could I bear it --

and I know, I know there are ways

of losing children, of seeing them stray off

among the trees even now, especially now!

Every fleet needed for its construction

the razing of an entire forest --

lost forests meeting on the tilting hills

of the Caspian, the Baltic, the Black Sea,

over the mountains of water the file of forests

comes. Your face is a mobile mischief,

do you know? Your eyes mocked before

they entreated, your lips rendered

both comedy and its dark twin

in microseconds, and your tongue

harried my mouth’s bays and inlets.

The Oberforstmeister of Kurland promised

the King ‘at least half-fabulous’ beasts

for the hunt, his forest measured

140,000 arpents and even on the swiftest mounts

horsemen could not traverse it

in a month. My mind runs fast

down its arpents and leafy corridors,

seeing no one, I should slash

tree-trunks to procure my safe return

but I can’t stop. My mind is running

on pure grief and pure love, I want you

to know this. The Forest of Othe

was so still you could hear a shadow

cross a face at 60 leagues distance --

it had linked the Lyons Massif with

the Woods of Gisors but after a hurricane

levelled a million trees in 1519 the diligent

peasants moved in with plows and those forests

were never reunited. And

the forests of Finland, have you thought of those?

All the way to Archangel and the White Sea?

They can show you how you were

before these excuses. What can you do

about this, your exigent look said

in the doorway, I am going do you realize

I am going? And that both of us will survive this?

When the Swedes needed cash they cut down

the forests of Pomerania, the result in

many cases is sand-dunes. This for day-trippers

is nice, in your rented Strandkorb there is room

for everybody, also for dressing and undressing

when the beach is crowded. In the forest of Morois

Tristan lies with Iseult, they are waiting

for the King her husband who will tell history

they were only sleeping. In

the Black Forest dwarf trees and greenheart

still flourish -- as for the Rominter Heide

it was so huge that most of its lakes

and forests were ‘held in reserve’,

not listed or even mentioned, so for generations

all that those lakes and forests could do was

grow uncontrollably in the imagination. I

would take you with me into the Rominter Heide

if you would come: there

each child we must not hurt will

wear a rose in sign of her ardent, forbearing

heart, in sign of his calm-eyed ascent through

our extreme, necessary years.

Introduction or preface

The young Don Coles was a sojourner, extending a period of graduate study at Cambridge into a dozen-odd ‘wander-years’ in central Europe and Scandinavia. He returned to Canada in 1965, in his mid-thirties, and only then began writing poems; his first book did not appear until 1975, and it was not until the appearance of his seventh, Forests of the Medieval World, in 1993, that his poetry began to receive the notice it deserved. Coles’ European interests and infuences served initially to ostracize him as a Canadian poet: his early books appeared at a time when Canada was determined to forge a literary culture it could call its own. Declining to follow fashion, he continued to write poems inspired as often by cultural artefacts and the pleasures of reading as by the personal: a painting, a line from a literary biography, a scene from a novel could provide the spark. He eschewed flashiness of any sort, rejected innovation for its own sake, and applied a highly concentrated craft to the serious contemplation of what it is to be human. This won him the deep regard of discerning readers, but not the acclaim lavished on some of his contemporaries.

In selecting for this volume, I thought it best to excerpt as little as possible and only where the excerpts are effective as self-contained poems. Not represented here are Coles’ two book-length sequences, K in Love (a series of verse love-letters inspired by the letters of Kafka) and Little Bird (an extended letter-in-verse to his late father). I have tried nevertheless to show something of Coles’ range -- the different kinds of things he does in his poems, and the different modalities in which he addresses his overarching subject: time’s passage.

Any artist must love what fuels his art, but Coles’ love for his subject is also his war with it: in one poem, he refers to time as a ‘catastrophe’; in another, as ‘Time, the enemy’. In his poetry one feels the tug of the past on the present, the ever-present tug of the future; pathos of hindsight, pathos of aging, but also the consolation of memory. And one feels the vertigo of time -- notably, in the haunting ‘Somewhere Far from This Comfort’.

Of particular interest to Coles are the arrested moments that survive in photographs, letters, journals: what they tell us, what they withhold, the signals they relay across years. Many of his poems begin in contemplation of a photograph -- usually from his own family album, but the example I have chosen (‘Photograph in a Stockholm Newspaper for March 13, 1910’) describes a family of strangers, nameless and likely long dead, about whom nothing can be known ‘except that once they were there’. Enigmatic, these people are ‘safe now from even their own complexities’ and they seem to the poet ‘miraculous’. Surviving in this one slightly blurred formal portrait, they present the illusion of having escaped life’s rough and tumble -- what Coles elsewhere calls ‘this old, hard business of meddling with time’.

Against such complexities, Coles holds an ideal of untouchedness, innocence. We see it in the pre-conscious waking state described in ‘Untitled’ (‘I had not sustained any damage at all yet. Whatever was special in me had not been dulled by use or exposure ...’) -- and in the tabula rasa of the hockey rink after the Zamboni has finished its rounds, in ‘Kingdom’. Given that life must always decline from such perfect states, the tension in his poetry is that of opposites to which he is differently attracted: wandering and restlessness with their associated risks, vs. stasis and patience with their promise of safety, reliability, serenity. Coles can change sides within a single poem: in ‘Botanical Gardens’, musing on the rooted constancy of trees, he experiences ‘sudden remorse’ at ‘not having lived patiently enough’, but soon decides this line of thought is pointless, admitting, ‘I never wanted/ to stay long anywhere, really.’ Still, he is haunted by shades of what might have been. Roads not travelled, words not spoken, lives cut short or otherwise unlived are invoked in ‘Someone Has Stayed in Stockholm’, ‘Marie Kemp’, ‘William, etc’, ‘Not Just Words but World’.

A secondary theme for Coles is the plight of the overlooked, the helpless, those who cannot speak for themselves. ‘Landslides’ is a series of compassionate, mostly one-way conversations with his mother in a geriatric care centre. ‘Mishenka’ considers the case of Leo Tolstoy’s illegitimate half-brother, who grew up illiterate and died a pauper. In ‘The Prinzhorn Collection’ -- a poem that has been compared to Browning’s ‘My Last Duchess’ -- a fictional curator writes a letter describing his museum’s current exhibition: drawings and writings by inmates of a 19th century German insane asylum, reportedly salvaged by a certain Doctor Prinzhorn from the files of a predecessor. (The Prinzhorn Collection is real, though Coles has simplified its provenance here.) Through the voice of this conflicted but not unfeeling curator, Coles describes actual drawings from the collection, and quotes passages from heartrending letters that were never mailed -- ‘derelict 100-year-old signals (airless cries, unlit gestures)’ that, in coming to light and being presented now as art, stand as both chilling indictment and exigent human truth.

Much has been written of Coles’ signature poetic voice -- civilized yet informal, poised between colloquial and literary. His poems seem thought-aloud, unfolding spontaneously, with hesitations, backtrackings, and parenthetical digressions that affect a conversational intimacy while guarding a personal privacy. Their casualness is artful: the poems are much more worked than they appear. (One American poet-critic wrote me, ‘Reading Coles has been interesting, in that lines that I thought were insufficiently charged the first time through, seem tighter and more satisfying each time I go back to them.’) Rhyme, present in some of the earlier poems, is so unobtrusive that an inattentive reader could miss it altogether: see ‘Mishenka (I)’, ‘William, etc’, and ‘Sampling from a Dialogue’ (the latter actually a disguised Petrarchan sonnet in which, ingeniously, formal moves of the poem slyly echo emotional moves of the couple depicted.) Coles is also capable of seamless and inspired vocal shifts: in ‘Codger’, note how we start out looking at the old man from the outside, but gradually are drawn into his world, until we find ourselves overhearing his very thoughts.

For all that, there’s a curious elasticity to Coles’ exactness. His fondness for reworking poems is well known: some exist in as many as five or six published versions. While successive revisions show inarguable improvements, each version has its own virtues and its own integrity of logic and effect. The poem remains recognizably itself, but a line-by-line comparison with the previous version will reveal subtle but significant variation throughout (including, often, all new line-breaks). One cannot easily splice versions in the interest of saving preferred bits from each; they resist combination. What will future anthologists and editors make of this? For Coles, the latest version of a poem is the definitive one; but the existence of multiple versions will, I suspect, ultimately be recognized as part of the richness of his art.

—Robyn Sarah

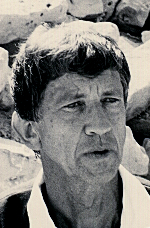

Don Coles was born on April 12, 1927, in the town of Woodstock, Ontario.

Coles entered Victoria College at the University of Toronto in 1945. He did a four-year history degree, then a two-year M.A. in English, spending two undergraduate summers in Trois-Pistoles, Quebec, learning French, and one summer travelling in Europe. He had several courses with Northrop Frye and Marshall McLuhan, whom he recalls as the best teachers of his life. In between the two M.A. years, he spent a year in London working in a bookstore, then enrolled at Cambridge from 1952 to 1954, and upon graduating was awarded a British Council grant to live in Florence for a year. It was in Stockholm that he met Heidi Golnitz of Lubeck, Germany, whom he eventually married; they lived in Copenhagen and Switzerland before coming to Canada with their daughter in 1965—supposedly for a visit, but they stayed.

It was only around 1967, in tandem with teaching, that Coles began writing poems. His first collection appeared in 1975 when he was forty-seven. It was followed quietly by several others, but he resisted becoming a public poet-persona. He was sixty-five when Forests of the Medieval World won Canada’s premier literary award. As a poet, Coles has always marched to his own drummer. He was never enamoured of the modernist poets, looking instead to what he has termed the ’Hardy-Larkin line’, those who were able to move their art back towards accessibility and the general reader. Besides his ten poetry collections, Coles has, since retirement, published a novel and a collection of essays and reviews, and translated a collection by the late Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer.

Coles resides in Toronto, but has lived close to twenty years in western Europe, with sojourns in Munich, Hamburg, and Zurich besides cities already mentioned. A deeply private man, he lists family first among his pleasures.

Robyn Sarah was born in New York City to Canadian parents, and has lived for most of her life in Montréal. A graduate of McGill University (where she majored in philosophy and English) and of Québec’s Conservatoire de Musique et d’Art Dramatique, she is the author of seven poetry collections and one previous collection of short stories, A Nice Gazebo, published by Véhicule in 1992. The same year, Anansi published The Touchstone: Poems New and Selected, a collection of her poetry spanning twenty years. Robyn Sarah has also recently published a collection of her essays on poetry, entitled Little Eurekas.

The Porcupine's Quill would like to acknowledge the support of the Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. The financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) is also gratefully acknowledged.